The Black Lives Matter movement is in full swing.

135 days. The movement lives. #Ferguson

— deray (@deray) December 22, 2014

I’m trying to practice being a good ally. For me, this means amplifying Black voices leading the movement and speaking mainly to my White friends about systemic oppression. I consciously follow more Black voices on Twitter and retweet them when they speak about this movement. At the same time, I tend to avoid retweeting sympathetic statements about the protests by White people, as it’s just not their / our movement to lead.

What can white Allies do:

•Amplify black voices

•Raise money in affluent circles

•Decline interviews

•Focus on support roles— The Good Witch of the South (@ForRevolution) December 5, 2014

Aside from doing my part to reduce the White noise in the Black signal around #BlackLivesMatter, I remember what Teju Cole wrote about the White Savior Industrial Complex. He focused on foreign policy and charity by Americans to impoverished and disaster-saddled countries, but I think his advice is applicable to White interference in neighboring communities:

To do this would be to give up the illusion that the sentimental need to “make a difference” trumps all other considerations. What innocent heroes don’t always understand is that they play a useful role for people who have much more cynical motives. The White Savior Industrial Complex is a valve for releasing the unbearable pressures that build in a system built on pillage. We can participate in the economic destruction of Haiti over long years, but when the earthquake strikes it feels good to send $10 each to the rescue fund. I have no opposition, in principle, to such donations (I frequently make them myself), but we must do such things only with awareness of what else is involved. If we are going to interfere in the lives of others, a little due diligence is a minimum requirement.

What is the equivalent in the United States? We witness police in segregated suburbs and the country’s largest city evading judgment with the complicity of our “democratic institutions.” Judgment came to Mike Brown and Eric Garner from a gun and from muscular arms, but the system’s power saved Darren Wilson and Daniel Pantaleo from the process of judgment. The justice system is used as a tool to dismiss state violence against Black people in 2014 as in 1931. My due diligence question right now is: why has this not changed?

Something is happening in US society, behind what goes on in the White House and Congress. Tens of millions of people vote for radically right-wing Representatives and Senators every two years, but they express their values in their communities every day. Polarization doesn’t just happen in DC – it plays out in how our public infrastructure chooses winners and losers, and who pulls its levers. We seem to disintegrate in ways that matter to things like the police and the military, not just by race or income level.

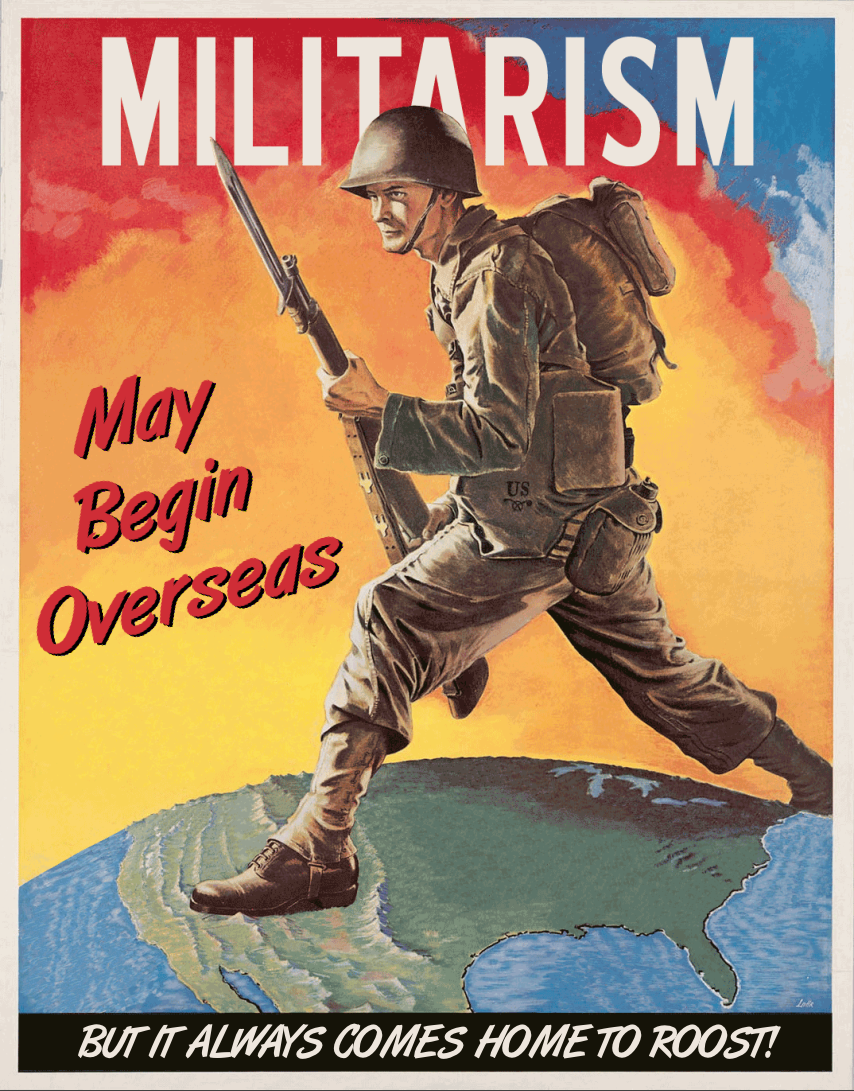

Are we entering a “Praetorian society?” This phrase first came to my attention a couple years ago, in this article on the rise of the Praetorian class in the United States. It’s a rather libertarian view of the world, but I think it has basic merit. According to author Pete Kofod, the Praetorian class includes

members of the Armed Services, federal, state and local law enforcement personnel as well as numerous militarized officials including agents from the DEA, Immigrations, Customs Enforcement, Air Marshals, US Marshals, and more. It also includes, although to a lesser extent, various stage actors in the expanding security theater such as TSA personnel. The main mission of the Praetorian Class is to keep the order of the day. This requires displaying an intimidating presence in their interactions with the Economic Class.

Many returning veterans from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq transition to careers as mercenaries abroad – staying in the war game. War machines are given freely or sold subsidized to small-town police departments. My hometown police department has two UAVs and doesn’t know why.

Samuel P. Huntington breaks down the differences between a “civic” and a “praetorian” society. A praetorian country looks like:

fragile, fleeting forms of authority, charismatic leaders, military junta, populist dictator. All forms of government whirl and change in unpredictable manner. Politics and political participation are neither stable nor institutionalized.

Huntington’s definition focuses on the experience of a whole nation-state, while Kofod’s describes a concentrated segment of our society. Since Huntington’s praetorian society relies on a less-governed society with weak institutions, this does not describe the United States on its surface, not even after a bit of digging. At ground level, however, we can see a hollowing and a shifting of social and economic structures. The ties within and between our institutions are breaking without shuttering the institutions themselves. They may undergo a renewal of purpose in favor of our corporatized society, or they teeter at their foundations while showing a strong face to the public. So instead of looking to the White House to answer the praetorian question, I want to start with the associations between people in the country.

That’s where those tens of millions of Tea Partiers and countless milquetoast liberal enablers build the praetorian society. From “I Can Breathe” to “All Lives Matter,” they divert the organizing work of critical examination and repair of society’s foundations. They hobble our potential. Power and capital are concentrating in the hands of the same people. They are real and they hang out mostly with each other and give each other guns and jobs.

I never considered what the opposition to a “civil / civic” society is. It seems to be praetorian. Code for America supports programs and rhetoric that emphasize civic institutions, like “civic technology” and government itself. I have not heard or read anything from our colleagues that outlines what kind of world we are working against.

The civic technology movement needs to identify just what we are working towards, in order to understand our movement’s antagonists. They are a movement and power themselves. If we are brave enough to publicly research and examine the praetorian society, we can better help others understand and enunciate the importance of alternatives.